John Lescroart is a New York Time bestselling author known for his series of legal and crime thriller novels featuring the character Dismas Hardy. His novels have sold more than ten million copies, have been translated into twenty-two languages in more than seventy-five countries, and fifteen of his books have been on the New York Times bestseller list. In addition to more than twenty novels, Lescroart has written several screenplays, and appeared as a contestant on the game show Tic Tac Dough in 1979, as well as on Joker’s Wild, Blank Check and Headline Chasers. Under Crow Art Records, Lescroart has released several albums, including a cd of piano versions of his songs performed by Antonio Gala. He has for some time been writing and living in Davis, California. He is an original founding member of group International Thriller Writers. He has a new novel out, The Ophelia Cut and it sounds like another great one.

John met me at The Slaughterhouse, where we talked about his new release and the moral challenges his characters face within his fictions.

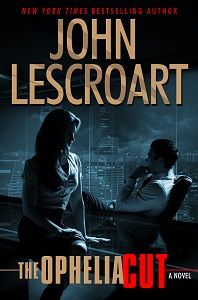

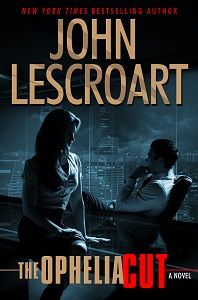

Tell us about The Ophelia Cut.

In THE OPHELIA CUT, Dismas Hardy takes on the legal defense of his brother-in-law, Moses McGuire, who is accused of murdering Rick Jessup, a young San Francisco politician who allegedly raped McGuire’s stunningly beautiful daughter Brittany. Complicating matters considerably, for Hardy as well as for his best friend, homicide lieutenant Abe Glitsky and Hardy’s law partner Gina Roake, is the fact that Moses is an alcoholic struggling with the aftermath of an event (recounted in THE FIRST LAW) known as the Dockside Massacre, in which, six years before, Hardy, Glitsky, Roake and McGuire were forced into a gun battle with a group of corrupt San Francisco private security forces that left five men dead. When police investigating the murder of Rick Jessup close in on McGuire as their main suspect, McGuire begins to drink again and to come undone. As the trial progresses, will McGuire inadvertently reveal the fatal secret that links him to Hardy, Glitsky and Roake, ruining all of their careers, if not their lives?

In THE OPHELIA CUT, Dismas Hardy takes on the legal defense of his brother-in-law, Moses McGuire, who is accused of murdering Rick Jessup, a young San Francisco politician who allegedly raped McGuire’s stunningly beautiful daughter Brittany. Complicating matters considerably, for Hardy as well as for his best friend, homicide lieutenant Abe Glitsky and Hardy’s law partner Gina Roake, is the fact that Moses is an alcoholic struggling with the aftermath of an event (recounted in THE FIRST LAW) known as the Dockside Massacre, in which, six years before, Hardy, Glitsky, Roake and McGuire were forced into a gun battle with a group of corrupt San Francisco private security forces that left five men dead. When police investigating the murder of Rick Jessup close in on McGuire as their main suspect, McGuire begins to drink again and to come undone. As the trial progresses, will McGuire inadvertently reveal the fatal secret that links him to Hardy, Glitsky and Roake, ruining all of their careers, if not their lives?

Meanwhile, Brittany becomes involved with a shadowy figure named Tony Solaia, a federally-protected witness who weaves through the action of the novel like a ghost. At the same time, Hardy uncovers troubling connections in the life and work of Rick Jessup that raise the question of how many other people may have a reason to have wanted him dead. Finally, in a feat of legal legerdemain that is staggering both in its implications and its simplicity, Hardy finds a witness who at a shocking stroke dismantles the basic theory of the case.

But at what price?

A complex morality tale that pits lifelong friends against one another in the crucible of the courtroom, THE OPHELIA CUT presents Dismas Hardy with his most personal case to date, and one of his most complicated, where the ever-dangerous truth is not always a stepping stone on the path to justice, and where long-buried secrets still have the power to redeem or destroy.

The themes of THE OPHELIA CUT are betrayal, family, loss of innocence, rape, date rape and vigilantism. The center of gravity in THE OPHELIA CUT is Brittany McGuire, a beautiful and confused 23-year-old recent college graduate who shares the all-too-familiar story nowadays of young women getting out of college and being forced to accept work as a barista in a coffee shop. Brittany is very much a young woman of our age, and her struggles as she tries to define and find herself are a core and compelling component of this book. But THE OPHELIA CUT also features two longstanding male friends, Dismas Hardy and Abe Glitsky, both of whom inhabit the very hard world of criminal law. The legal battles and moral issues that infuse the book should also appeal to anyone who enjoys “courtroom dramas.” And in fact, this book walks the thin line between mainstream and genre fiction.

This book began under the title of THE TARGET and originally was going to center around the character of Tony Solaia, a person in the federal witness protection program. I wrote well over a hundred pages before I realized that the story was not moving in a direction that I found important. The idea of a big book about the legal and emotional issues surrounding rape kept flirting around the edges of my consciousness, and so – much to my own dismay – I jettisoned my first hundred original pages and committed myself to the new and better idea that became THE OPHELIA CUT.

This book has many themes, both personal and universal: A young woman’s casual attitude toward dating and sex ensnares her in a terrible relationship with a truly dangerous man – every parent can identify with this scenario. When this man drugs and then rapes Brittany, her father’s rage leads him to seek revenge. Meanwhile, the young man works as Chief of Staff to a politician, Liam Goodman, with plenty of dirty laundry in his closet – Goodman has been defrauding the US government for years; he has also been in business with a Korean businessman named Jon Lo, who is a big player in San Francisco’s international sex slavery/human trafficking trade. There are big issues and evil people everywhere you look in this book.

But compassionate and ethical people also abound – Dismas Hardy, his wife Frannie, their daughter Rebecca, Wes Farrell (San Francisco’s District Attorney) and his girlfriend Sam, Hardy’s law partner Gina Roake and his best friend police lieutenant Abe Glitsky. These people lead “normal” lives: they cook, tell jokes, go out to dinner, try to do the right thing often in tremendously adverse circumstances. They protect one another, they reach out to others, they persevere. They know that there are no easy answers and that life is ambiguous and yet worth living.

Also, and critically, these good people had to break the law in the past to protect the people they love. They didn’t do it blithely; they did it because there was clearly no other way. And as much as they love their lives, they’re living with the fact of having done something they dearly wish they hadn’t had to do, and broke the law to do it. What makes this book distinctive is the intertwining of these personal and public issues in a way that makes the story resonate as universal and true to real life.

To what extent do you think revenge is lawless justice?

Though I understand and to some extent empathize with the urge for revenge, and think that it provides very fertile soil for fiction, in real life I am not in favor of it at all. It may, as you indicate, provide a sense of justice, but it is usually not justice under the law. In other words, it is lawless. And why do not laws usually embrace the concept of revenge? Because hundreds if not thousands of years of human experience have proven that the most common result of revenge is not justice, but a cycle of more revenge. If you kill my relative, then true revenge demands that I kill one of your relatives; and then, of course, you feel the need to avenge that violence with more violence of your own, and so on down through the years. This universal truth was perfectly expressed in ancient Rome by the statesman and philosopher Lucretius, whose quote on the topic serves as the epigraph for The Ophelia Cut: “Violence and injury enclose in their net all that do such things, and generally return upon him who began.”

Fiction often challenges institutions, be they legal structures or political ones. Thinking of St Dismas, do you think within religion there is absolution for criminals and if so what does it entail?

I think that one of the greatest inventions of mankind is the twin concept of sin and forgiveness. Since we are all imperfect, it’s inevitable that we will all sin. Then, lest we be cut off from salvation, from our connection with the rest of humanity, it’s essential that sin be forgiven, that we be given absolution. Religions that have institutionalized this concept have proven to be very successful in controlling their adherents, and in giving them something to believe in. Saint Dismas, the so-called Good Thief, was obviously a criminal who had committed at least one capital crime. He had been sentenced to death, to crucifixion. As he was on Calvary, hanging on the cross near Jesus, he asked for absolution from his sins. He would still be punished for them, but the sins themselves would be forgiven. Jesus told him that “this day, thou wilt be with me in Paradise.” And hence for Catholics, he became Saint Dismas. At the same time, Christ took the opportunity, as he hung dying on his own cross, to show by example the power and validity of absolution. He absolved Dismas of his sins, and promised him a permanent place in heaven. The lesson is clear: no matter what sins a person has committed, absolution is possible. It entails acknowledgment of the sin and a sincere desire for forgiveness. After which, the soul is clean again.

Who are your literary influences?

This is an easy question. I’ve been a voracious reader my whole life, and it sometimes feels as though everything I have read has been an influence in one way or another. I distinctly remember that my first real novel was Tom Sawyer when I was halfway through 3rd Grade. Still in grammar school, I was completely sold on the Landmark Books, biographies of famous people from Babe Ruth to Lindbergh to Clara Barton (“Girl Nurse”). Then I was an English major in college, specializing in the Continental Novel in translation, and was immersed in the works of Tolstoy, Camus, Dostoevsky, Stendhal, and so many others. About the same time, for fun, I discovered Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Rex Stout (Sherlock Holmes and Nero Wolfe, respectively), and here suddenly we are getting into the people who truly influenced what I wrote and to some extent how I wrote it. I also wrote my first novel in college, and tried to inculcate into it some of the values of Hemingway and — to the degree they could be reconciled — Lawrence Durrell, author of the Alexandrian Quartet (four novels — Justine, Balthazar, Mountolive and Clea — which changed my entire literary world view). When I started writing modern mysteries, I devoured John D. MacDonald (Travis McGee) and Lawrence Sanders (“The First Deadly Sin,” etc.) then everything Elmore Leonard ever wrote. And then finally I was on the boards with my own voice. My last “conscious” influence over the past few years has been Patrick O’Brian and the Aubrey/Maturin series.

There are so many great whodunnits in crime fiction, perhaps the first great whydunnit is Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment. Do you think Raskolnikov is seeking guilt or redemption in the novel and how closely related are the two?

This is a real “English major” question, and my history at UC Berkeley makes me feel as though I should answer in a ten-page essay with footnotes! But here, if you don’t mind, I’ll just give you the short version. Raskolnikov is clearly one of the most ambiguous and interesting “heroes” in fiction. Though an intellectual of the first order, Raskolnikov is really what today we would call a sociopath. I think that to say he is “seeking” either guilt or redemption is to somewhat miss the point. When he commits murder, he is — to me — doing it more out of intellectual curiosity. He wants to know how its feels, how the knowledge that he’s taken a life makes him feel. I never really got the sense that he was concerned for the salvation of his soul so much as that he wanted to experience the feeling of guilt so that he

could understand it intellectually. I don’t believe that Raskolnikov’s concept of redemption was spiritual, either. He knew that punishment would not bring him to a state of redemption. What he wanted to know, again, was what it felt like to know that his punishment was deserved. As to the second part of your question: how closely related are guilt and redemption? Well, without guilt one has no need of redemption but, as we discussed earlier, the element of absolution is necessary as a bridge between the two.

How would you like to be remembered?

This one’s easy. Though I’m proud of my books and my career, and hope they continue to be read for many years, I’d like to be remembered not so much as an author as an honest and loyal friend, a loving and faithful husband, and a good father. The basics.

What do you make of the E Book revolution?

Let’s start with the positive. It’s wonderful that so many people are reading, in whatever format. Kindle and Nook and all of their brothers and sisters are certainly convenient, lightweight, and eminently usable. More books than ever before are more easily accessible — the push of a button! — than they had ever been. Authors are able to see their own work disseminated to the public more quickly than ever before, and with no middleman in the way to drive up consumer prices. So, in all these ways, the E-Book revolution is a positive force.

That said, for there are significant drawbacks. The very term “author” has become devalued to a great extent. It used to be that an “author” was a person who had published a book that had been chosen, edited, vetted, and published by industry professionals with admittedly subjective, but nevertheless relatively uniform standards. Now, especially with E-Books, an “author” is someone who has put their own book into the marketplace. All of this, which used to be called “vanity publishing,” is now generally included in discussions about published work, and I don’t think this is a service to anyone. Last year saw the “publication” of 340,000 titles, the vast majority of them mostly unread. I think that the marginal quality of much of this unedited work devalues books in general.

Next, the mainstream publishers have done authors a great disservice by not standing up to Amazon (and other E-outlets) about the timing of the release of published works. In the days before E-Books, the hardcover book came out usually a full year or more before the book was available as a paperback, in a cheaper format. So fans of authors would spend extra to buy the hardcover if they wanted to read a book right away. In the E-Book environment, publishers caved in to Amazon’s demands to release the E-Book on the same day as the hardcover, at roughly one-third the price. Of course, a huge percentage of hardcover buyers started buying the cheaper, downloaded book. While this might sound good to authors — after all, more books were being sold — in reality this resulted in severe cuts in income, since the royalty on a $12.99 book is significantly lower than the royalty on a $26.99 hardback. On top of that, the royalty as a percentage of the sale price is far lower in E-Books than in hardcover, so that even if you’re selling more of your books, you’re making less money.

In all, I would say that the E-Book revolution is here to stay, but that it has not generally been a positive thing for authors thus far.

What are you working on at the moment?

I’m working on my next novel, due to come out in May of 2014. It’s a Hardy/Glitsky book tentatively called The Keeper, and is interesting in that I don’t see it turning into a trial book. Glitsky, about six months into his retirement, is getting a little bit bored with his life, and with Wyatt Hunt (Hardy’s private investigator) on an extended honeymoon in Australia, Hardy asks Glitsky to look into the disappearance of one of his prospective client’s wife. And he doesn’t get too far down that path before unsettling things start to happen.

How much does Dismas Hardy balance and resolve moral conflict in your fictions?

One of the things that makes Dismas Hardy an interesting and sympathetic character is that he is constantly trying to balance (and understand) his inner life while at the same time dealing with the professional demands of being a criminal lawyer. Every one of his cases involves not just a crime, but moral ambiguities that need to be addressed — or at least Hardy feels as though he needs to address them. In real life, of course, many if not most lawyers hew to their strict obligations as attorneys. Because of their oaths, they need to stay within certain well-defined ethical boundaries, but these seemingly endless questions of ethics vs. responsibility vs. morality are ever-fascinating; and Hardy labors to give each part its due. This is more than most lawyers attempt, but it makes for a richness in the books that identifies them as fiction at the same time as it (hopefully) provides a deeper satisfaction with the outcome, especially when these conflicting concerns all resolve in a believable and powerful way. In any good story, the order of the universe falls apart and then is restored, and Hardy’s unflinching connection to what is moral and just, as opposed to what is simply and strictly legal, is a critical component of this restoration of order.

What advice would you give to yourself as a younger man?

What a fantastic last question! The advice I would give myself is probably what I’ve tried to convey to my two children: Life is long. Be patient and keep on trying, since persistence is as important as talent. Have as much fun as you can. Love with your whole heart.

John thank you for a great and perceptive interview.

Links:

Links:

Pre-order THE OPHELIA CUT in Hard Back:

Amazon.com

Amazon.co.uk

Barnes & Noble

Simon & Schuster

IndieBound

Pre-order THE OPHELIA CUT as an eBook:

Apple iBookstore

Barnes & Noble

Amazon.com Kindle

Amazon.co.uk Kindle

Simon & Schuster

Find John at his website, on Facebook, and on Twitter

Slash is a film that will take you on a journey between fantasy and reality. It’s – as the name so obviously indicates – a slasher film, but it’s also a coming of age film and it’s also a mystery.

Slash is a film that will take you on a journey between fantasy and reality. It’s – as the name so obviously indicates – a slasher film, but it’s also a coming of age film and it’s also a mystery.