Chad Eagleton is a crime writer and editor. He is also writing a biography of Shane Stevens. Stevens is a highly underrated and widely unknown author, whose works demonstrate a fluency and realism that make them stand out from the crowded world of crime fiction. By Reason Of Insanity, a gruelling study of madness and criminality, is Stevens’s most famous work, while Dead City is a classic piece of gritty fiction, and they’re arguably Noir, equally unorthodox, and convey a real sense of the criminal underworld. Stevens’s versatility coupled with his secrecy as an author has made him the subject of various inaccurate speculations over the years, and there is hardly any information about him. Chad is conducting meticulous biographical research into Stevens.

Chad met me at The Slaughterhouse where we talked about why Stevens’s works distinguish themselves, and the commentary his novels offer on the great American Dream.

How do you think the novels of Shane Stevens distinguish themselves from the body of crime fiction?

Couple of ways. I think Stevens’s work perfectly encapsulates a period of American History, the vanished street life of the early 1960s through the late 1970s. However, that’s not me saying that I think his work is of mere historical interest, like DeFoe’s Journal of the Plague Year let’s say. It’s far more than that.

When crime fiction is operating at its best, it should not only be confrontational but it should be social fiction that deals honestly with real world issues that are going on right here, right now, right outside your door. Unfortunately, I think crime fiction has gotten the Times Square treatment–clean it up so it looks good for the tourists and keep the riff-raff out of sight. The narrative we are usually fed passes through this white, middle and upper class filter. So we either get this violent, wish fulfillment junk that’s supposed to titillate us on our lunch break but is no more realistic than a comic book while being half as fun. Or our American Dream middle class fantasy is shown under attack from minorities or the poor or some greedy good-for-nothing that wants what we’ve worked so hard far. Stevens’s work was different though. It dealt truthfully with things like race, poverty, class, institutionalized violence. All the issues that are back at the forefront of our national dialogue after decades.

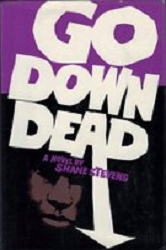

Stevens has quite a range of material in his fictions, from the incisive exploration of a psychopathic mind in By Reason Of Insanity to the hard boiled Dead City, from Go Down Dead to The Anvil Chorus, all of them real, all different. Given your previous comments about his novels, to what extent may they be read as a dark, anti-popularist commentary on the hollowness and corruption at the heart of the great American Dream?

That’s exactly what they are. I mean, Stephen King didn’t say Stevens wrote three of the finest novels about the dark side of the American dream for nothing. We’re told the world functions as a meritocracy, and it does not. We’re promised that success and financial security follow as a natural result of hard work, and they do not. The system is rigged to keep you down—has been for a long time. There is a hopeless desperation to poverty that so few in the United States can really understand unless they’ve been in the trenches—like Stevens.

That’s exactly what they are. I mean, Stephen King didn’t say Stevens wrote three of the finest novels about the dark side of the American dream for nothing. We’re told the world functions as a meritocracy, and it does not. We’re promised that success and financial security follow as a natural result of hard work, and they do not. The system is rigged to keep you down—has been for a long time. There is a hopeless desperation to poverty that so few in the United States can really understand unless they’ve been in the trenches—like Stevens.

You know, Shane was born in Hell’s Kitchen and grew up white in Harlem. I have some copies of some letters he wrote to his first agent that are just heart-breaking, asking if he knew of any jobs because he needed money for rent and was trying to keep his family together, asking if he he’d heard anything from the contest because he needed $1k to stay out of jail. So he got it. He understood that poverty affects all your decisions. Poverty strips you, the worker, of your bargaining ability. Poverty erodes self-esteem and degrades the acceptance of your peers. Poverty devastates your health. Poverty allows alcoholism, drug use, and abuse (both physical and sexual) to flourish—contributing to a mental disconnect from our species. This disconnect reinforces the terrible notion that the world functions only on the level of power and its exchange—one of  the main re-occurring themes in every single one of Shane Stevens novels.

the main re-occurring themes in every single one of Shane Stevens novels.

This rigged systems taints our ability for compassion. The biggest part of compassion comes from the ability to set aside your own experience and really understand what someone else has experienced. But when all that is being gamed, well, then poor is framed as a “choice”—which is bullshit because no one would ever choose to be poor. But you see, when poor is framed that way, then the poor can be scapegoated to distract you, and the criminal can be treated simply as the aberration that won’t do what he’s supposed and so ruins it for everyone.

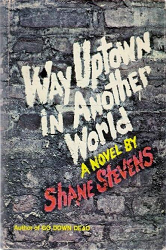

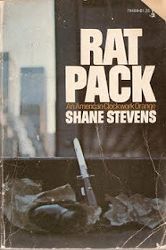

It’s easy, I think to be sidetracked by the race issue with Stevens’s early books. Go Down Dead, Way Uptown In Another World, and Rat Pack all feature African-American characters and, at least partially, take place in Harlem. But race is, I think, meaningless to Stevens. Race is another distraction from class. A beautiful example of this occurs in Rat Pack when the gang breaks into the empty courthouse and finds a white repairman working alone. As the tension escalates, Stevens jumps between everyone’s different points of view and we see clearly how both the black youths and the white repairman are  essentially in the same place, struggling to get by and feeling like they have no options, while thinking essentially the same thing about each other: you’ve got it so easy and it’s your fault I haven’t had that success and financial security I was promised.

essentially in the same place, struggling to get by and feeling like they have no options, while thinking essentially the same thing about each other: you’ve got it so easy and it’s your fault I haven’t had that success and financial security I was promised.

I also have a copy of a letter Stevens wrote to Charles Harris that lays it all out clearly: “What’s happening is that this is a class struggle going on in this insane country. Of which white racism is a part. What counts is not skin color but life style: money, Charles, money. The question is how you live—that determines what side of the gun you’re on. Now the people of all colors who are poor are beginning to move and they’re moving against those who keep them down. Middle class America: with its false liberals, its private ownership of everything needed to live, its slave state mentality and racist theology…”

Much of the greatest writing is about divergence and transgression. In Peter Shaeffer’s play Equus, about a schizophrenic blinding horses, the disillusioned psychiatrist who is treating him, says, ‘passion is about getting your own spirit through your own suffering, that is what that boy has done here,’ as he rejects his training. Stevens writes a lot about the edge of normality and shows how norms are shaped by social lies and repression. How much do you think that as society is engineered towards a conformity to a norm that is addictive and deluded, writers have duty to challenge and subvert that ideology?

Society is engineered toward conformity because conformity is comforting. That’s how our monkey brain is wired. It’s scary and dangerous to be the monkey who leaves the forest floor and the troop to see what’s on the other side of the river. Unfortunately, conformity also makes it easier for us to be controlled. I mean, what’s one of the first things you learn in school? How to stand in line and follow the person in front of you, right? Or where you and everyone else goes when a bell rings. And conformity too is a beloved tool used to sell you junk you don’t need. All of which in turn plays into our resistance to change and our deep hunger for continuity. Deeply, deeply human stuff we’ve been dealing with and trying to figure out since we were capable of trying to figure anything out really, right? I mean, the entirety of Buddhist thought is about how to deal with our resistance to change and impermanence.

But none of that—conformity, resistance to change, blind need for continuity—is useful to our growth or progress as either a person or as a society. It’s like Eugene Debs said, “If it had not been for the discontent of a few fellows who had not been satisfied with their conditions, you would still be living in caves. Intelligent discontent is the mainspring of civilization. Progress is born of agitation. It is agitation or stagnation.”

So I absolutely believe challenging and subverting conformity are part of the writer’s duty. A lot of people say a writer’s job is to be a professional liar. No. Stories are how we convey knowledge, they’re how we make sense of tough things, and they’re how we confront what should be confronted. I think a writer’s job is to tell the truth and the truth is always confrontational. Even if the story you’re telling is wrapped in bright shell of fantasy and make-believe, you should be able to crack that bastard open and find the truth in the center. That’s what I think the old writing adage “write what you know” means. What you know is the truth about your world, about your society, about your government, and about being human.

You know, to bring it specifically back to Stevens, I’m reminded too of a brief mention Jo LeCoeur gives Stevens in her article on John William Corrington and his contribution to the English Department as LSU. She writes, “Beatnik-attired, Bread Loaf Fellow Shane Stevens was on stage in spring 1970, his reading calling for armed rebellion against the white power structure for sending Puerto Ricans, blacks, and hippies to die in Vietnam.”

Rat Pack and Way Uptown In Another World are both gritty street novels, but to what extent do you find poetry in Stevens’s voice and what do you think his legacy is in the ongoing canon of crime fiction?

I think there’s poetry in everything he’s written:

“People dumping everything out the windows and buildings just crumpling down where they is. Must be hundred million bricks out there all worn and useless. Like mostly everything round here. Couple kids playing in the garbage and watching out they don’t step on broke bottles. They think this just a game what little kids play till they is grow up. They don’t know that what they whole life is going be. Just garbage and broke bottles.” –Go Down Dead

“Ginny never really had a chance. The sick got her and the misery got her and then the dead got her. She didn’t know anybody much and she was scared of all the paper stuff and she was too proud to ask other people for help. She was a Southern girl who didn’t understand the strange and easy ways of the North and she never got used to the cold.”—Way Uptown In Another World

“I have been shot, stabbed, beaten, gassed, stomped, whipped, jailed and had acid thrown on me. I have smelled death, seen its shadow and heard its cry. Violence has been my natural playground, and I know a little about it. And about the darker side of violence too, the violence that is within oneself. It’s just beneath the surface, lurking there, waiting, always ready to smash and destroy. Within each of us is this terrible beast; its screamings are maddening and, sometimes, unbearable. Then the violence erupts. The results are always tragic.”—The White Niggers of the 70s

“The girl in my building is running scared.”—A Day Like Any Other Day in Junk City

“In the crashpad existence of most East Village writers, probably the only thing in common is the fierce determination to write, to shake, to move minds, whether it be on paper, film, stage or brick wall.”—The East Village

As far as his legacy? That’s hard to say. A lot of times, it’s hard to measure influence directly. But, probably and unfortunately, not much right now. Especially in the States where pretty much everything except for By Reason of Insanity is out of print.

As far as his legacy? That’s hard to say. A lot of times, it’s hard to measure influence directly. But, probably and unfortunately, not much right now. Especially in the States where pretty much everything except for By Reason of Insanity is out of print.  I think he’s mostly a footnote or simply that guy Stephen King mentioned in The Dark Half.

I think he’s mostly a footnote or simply that guy Stephen King mentioned in The Dark Half.

It would help, I think, if his work would get reprinted in the States. I don’t know when that’ll happen though. A while back I put Lee Goldberg in touch with Shane’s agent. Lee wanted to release Dead City as an eBook through his Brash Books imprint but the agent relayed a “pass”. Which is a damned shame, but what are you going to do? Stevens being mostly forgotten is the main reason I started researching the man and working on a biography in the first place.

Thank you Chad for an informative interview.

Bio:

Bio:

Chad Eagleton is a Spinetingler Award nominee and a two-time Watery Grave Invitational finalist. He formerly served as a reader for Needle: A Magazine of Noir and as co-editor for the Beat To A Pulp webzine. His work is available in print, ebook, and online. Most recently, he completed Hoods, Hot Rods, and Hellcats, a 1950s-themed crime fiction anthology featuring an introduction from counterculture legend Mick Farren (Amazon US and UK). He has several new works forthcoming and is, in fact, still working on his Shane Stevens biography. In the meantime, join his fray at: dimestoreriot.com and find him on Twitter here.