Terry Irving is a journalist and an American four-time Emmy award-winning writer and TV producer. His novel, Courier, is a motorcycle thriller in which the protagonist realises people are trying to kill him and he doesn’t know why. During his career Terry met

Hunter S. Thompson, and his article ‘A Long Night With Hunter Thompson’ is published here, with the author’s approval. Terry met me at The Slaughterhouse where we talked about the novel and modern America.

Tell us about Courier.

I think Courier is exactly the book I hoped it would be. It’s a flat-out motorcycle thriller–Three Days of the Condor meets Easy Rider—a Hitchcockian plot like North by Northwest where a private person suddenly realizes that people are trying to kill him and has to work out who, and why, and how to stop them. It’s my first novel but the dialog and descriptions feel right to me and a real sense of danger and escape comes through. It was always intended to be a book that you’d see in an airport kiosk and pick up to get you through a long flight.

I think Courier is exactly the book I hoped it would be. It’s a flat-out motorcycle thriller–Three Days of the Condor meets Easy Rider—a Hitchcockian plot like North by Northwest where a private person suddenly realizes that people are trying to kill him and has to work out who, and why, and how to stop them. It’s my first novel but the dialog and descriptions feel right to me and a real sense of danger and escape comes through. It was always intended to be a book that you’d see in an airport kiosk and pick up to get you through a long flight.

I’ve been working in Television News for 40-some years and writing for the past 25. I guess I was fairly cocky but I thought I could write a novel and, during a period of unemployment in 2010, told myself it was time to “put up or shut up.”

I finished the first draft in about 10 or 12 weeks and then got sidetracked by day labor at Retirement Living TV and Bloomberg TV. (Bloomberg was like writing in a foreign language from midnight to noon, felt like driving six-inch nails into my temples, and convinced me that it was time to hang up the tie and suspenders.)

Some things in the book only came to me while I was writing. No, I’m not one of those people who plan everything before they begin nor am I a member of the creative writing community who believe that the characters should tell me where they want to go.

Well, they fairly often did tell me where they wanted to go but I still don’t believe it.

I didn’t realize that the days that I lived as a motorcycle courier in 1973 would turn out to be “historical.” The more I wrote, the more I realized how much the world had changed. In 1973, everyone smoked everywhere, there were almost no women or minorities in television or any other business, Vietnam was 24 hours away instead of live in your face every moment. Washington, in particular, was a completely different city–much slower-paced and casual, more concerned with people than ideology. It was also much more corrupt, with the White House in direct and very invasive control of every branch of government and quite willing to use them for political purposes.

Yes, I was a motorcycle courier back then but I am not Rick Putnam–the protagonist of Courier. I took a first try at writing the book with me in it and gave it up for a bad job in a matter of hours. Rick is based on a picture of a young Nic Cage on a chopper along with bits and pieces of several correspondents and friends from the time. I can’t remember when he turned out to be a Vietnam veteran but that became the primary structure of his character. He is closed off, desperate to forget the terrible memories of war, refusing to accept any emotional relationships because too many friends died, and only able to clear his head by exhausting physical exercise or by taking his motorcycle to the very edge. To that point where you need to put every bit of your mind to the task of simply staying alive.

I know that feeling from riding but the most intense experience was when I took a race car course in Formula Fords. You come into a turn, time stretches, you see the puffs of smoke from the front tires, you watch the revs for your shift points and the track for the braking stripe and then you hit the groove into the turn, spin the wheel while the tires are still sliding, and then let up on the brake and feel the car turn itself as the tires grip the road again. After that, well, it’s the unbelievable feeling of an engine just kicking you in the back as you accelerate up the straight.

Sorry, got carried away a bit there.

That’s one of the things about Courier. I didn’t get chased through DC by Saigon street cowboys or find the proof of why Richard Nixon really resigned, but the colors, smells, sights, and sounds are all mine. I was 21 years old and every day is as vivid now as it was then.

Another character who began as a cipher turned into a real person. The Grey Man who has been assigned to hunt down and kill Rick, became a soldier who had been frozen inside during the first days of the Korean War when US troops fired on civilian refugees in desperation because they couldn’t tell them from North Korean soldiers. He dealt with the killing by creating silence and has continued to silence people for the CIA ever since. I certainly never intended him to have a love interest but that just happened when he walked through the door of the Seoul Palace for Christmas Dinner.

I never intended Rick Putnam to find love (or at least to be willing to open a tiny crack in his armor and let someone in) until Eve Buffalo Calf began to talk. The honest, brave, and loyal person she was–hell, I probably fell in love with her so I made damn sure that my primary character did. Courier is the first book of the Freelancer series and Eve will play a major role in all the books.

I didn’t want to write a book where bullets go flying everywhere and someone says, “Oh, it’s only a flesh wound.” (A spinning bullet actually burns the skin as it passes and is almost certain to become badly infected.) I didn’t want death to be a casual occasion and, in particular, I didn’t want Rick to take it lightly.

As I did the research, it turned out that the primary cause of PTSD isn’t the fear of being killed, it’s the traumatic experience of either killing another human being or having to deal with the possibility of killing another human being. Rick certainly doesn’t mind hurting people who have guns pointed at him but he puts considerable effort into trying to work out a way to get the hunters off his back without simply blowing them away.

So, what is Courier? It’s a fast-paced, hard-to-put-down thriller with a worthwhile hero, a realistic (and I believe, quite plausible) secret that the government is willing to kill to protect, a villain who is relentless and deadly but not cartoonishly evil, it’s a story about a man who is choosing whether to live or die, it’s a story about the people who you can count on to stand beside you when the chips are down.

But don’t get the wrong idea. It’s not some college thesis or mushy artistic fine literature. When the shit comes down, it’s a Kawasaki 500CC triple (the fastest and nastiest bike on the road) against a Datsun 240Z on some of the coolest racing roads anywhere.

(For those with a need for speed, I’m talking about Rock Creek Parkway after dark. Try it sometime.)

How is speed related to your writing?

There was one very specific day.

I had survived a very tough winter, riding a motorcycle every day in the worst weather. Sometimes it was so cold that my core temperature would drop and I’d be incoherent like an old wino (which I’m not, in case anyone is wondering).

Then, spring came. Just like that. Snap. It was March or April and the temperature had gone up into the 60’s, the roads were dry and free of salt (a very slippery substance if you’re on a bike.) I can remember coming down the hill into Rock Creek Park with 4 lanes of traffic whizzing along with curves and blind turns–a very dangerous place.

Suddenly, I just took off.

I was rocketing down the center line, doing about 80, and I just didn’t care. I wanted to reach the bottom down by the Kennedy Center, cross the 14th Street Bridge, and just keep going. Maybe Florida, maybe New Orleans, maybe LA. I had that bike so nailed that it was like flying. One guy flipped me the bird and I just waved as I shot by. Another driver tried to block me and I took him on the inside.

Damn, that was great.

But, when I got down to Kennedy Center, I slowed, turned, and rode off to whatever boring assignment I was supposed to be doing. Pickup at the White House, bring a powderpuff to Sam Donaldson at the Capitol, whatever. I did have an enormous grin on my face.

Three weeks later, after a limo almost took me out at Reno Road and 34th street (man that was the longest car I have ever seen! I thought it would never finish crossing in front of me) I went in to the courier company and said I was taking the next week off. The dispatcher said that no one could take that week off because it was the Daytona Motorcycle Races and the place would be empty if they allowed it.

So I quit.

Hitchhiked down the old 95 with Monkey Jungle and Pecan Heaven. Slept under people’s cars in the Motorspeedway Parking lot and drank Bottomless Cups of coffee for a nickel.

And heard that incredible, insane sound that shakes every bone in your body. The sound of 100 motorcycles with their engines screaming at 20% over maximum revolutions.

Then the tone deepens when the flag goes down and they all kick into gear and just begin to fly.

I still get goose bumps and that was forty years ago.

Well, that answers the question of whether speed was important to me. Now let’s see about the book.

I was never the rider that Rick Putnam is in Courier. I knew people like that–most of them either died or were broken into small pieces. There was guy in ABC Radio who would come in in the morning with his face all battered because he’d gone right through the woods to avoid the police on the GW Parkway. I did know a courier who had two drivers’ licenses and only used one for traffic stops. He owed thousands and thousands of dollars.

Speed is Rick’s savior. It so completely fills his mind that the memories of elephant grass, mud made of blood, and horrible screams simply disappear. Speed is a matter of control and concentration. Anyone with an overpowered bike can go fast and die like the morons out on the Beltway doing their rear-wheel stands at 75 mph. What’s harder and more interesting is to use speed as a measure of mastery–the faster you can go, the better your mind, your reflexes, your entire being is.

From the beginning of the book, Rick is running away. He’s running from the police, from the mundane world where he no longer fits, he tries to run away from Eve (who won’t let him,) and eventually, he lures his enemies into a speed challenge and destroys them. In the beginning, Rick believes that he can only remain sane if he leaves everything diminishing in the rear view mirror. What he finds instead is that there are people who love him enough to stay right in there with him no matter how fast he goes.

How has working in Television News shaped you as a writer?

First, I’m going to resist the easy joke about how sitting all day and writing TV copy has been a critical factor in my current 6 foot 4 inches and 330 pounds of rippling .. muscle.

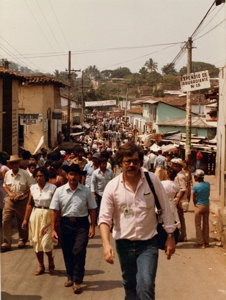

As you can see, for several decades, a steady diet of black coffee, lousy food, diarrhea, and 5 to 7 packs of cigarettes a day made me into a fuzzy-headed Adonis.

Of course, there was a cost for this and it wasn’t a decaying picture up in the attic. It was a decaying mind from the stress of working at the very top of the profession. I realize now that it really wasn’t rational for me to ignore bullets and rockets in Beirut but worry constantly about what Ted Koppel thought of my work. Ah well, there are many careers where your personal neuroses turn out to be an advantage (and result in four Emmy Awards).

To answer your question a bit more seriously, TV had a profound effect on my writing. In the beginning, I never wrote but I edited the copy of every correspondent whose package was being cut for the morning show or Nightline. Sometimes this resulted in quick revisions or corrections and other times pretty good battles where shouting and slamming doors were commonplace. I never actually hit anyone but actual fistfights were not unknown in the bureau where I worked.

This process toughens you up and forces you to make quick and correct decisions. If it was hard to get a reporter to change his story for a good reason, imagine what it’s like when you’re making it worse. This was a skill that improved throughout my career and in my later years at CNN, I would have 5 or 6 scripts come in at 5pm and need to return them in 30 minutes so that the field crew would have a chance to make air at 10pm. This would have been easy if it weren’t for the anchor’s nightly walks from his office to my desk and the whispered instruction, “This is crap. Complete crap. Turn it into something we can put on the air.”

At that point, I simply hung up on the reporter and field producer and completely re-wrote the script. Then I would send it back with a note saying that it was just some mild suggestions they might want to consider. Almost all of them simply did the new script and, honestly, they were usually better and often much better.

This is one of the most basic things that TV writing taught me: think fast and write faster. The field correspondents weren’t the only people to have their scripts savaged. I wrote directly for Aaron Brown, the anchor on that program, and he was one of the best writers I’ve ever worked for. I would go out, shoot a story, write a script and have about a 40% chance that it would be accepted, a 40% chance that he would rewrite it, and a 20% chance that he would simply cram it down my throat and “gently” request a rewrite. As I said, he was really good. Anything he wrote himself WAS better than anything I could write and the feeling when he approved of my work was wonderful.

There were other things I learned in television: there are at least a dozen ways to write any story, check the elements (pictures, interviews, etc.) before you write and then write to them, and, most important, “Failure is Death.” It’s a bit difficult to understand why, but people in television have a desperate need to make air with the undeniably best story they can do. I know that no one will believe this, but we really tried–under incredibly bad conditions (like writing your story on a Blackberry in a swamp) and unreal time constraints–

(“NY wants to know how long the piece is.”

“Tell them that when it’s 5 minutes to air, I’ll smack the final shot on and then we can find out how long it runs.”

“They’re not going to buy that.”

“They can either have the piece finished or know how long it is. Their choice.”)

–to create stories that presented an objective and understandable picture of the truth.

Honest.

So, after 40 years, what am I left with?

• Well, I have a pretty good ear for language. I actually sub-vocalize almost everything I write as I write it and the wrong word will simply ‘clunk’ and I’ll know to change it.

• From years of writing for different anchors and correspondents, I can change my style to another’s quite easily. It helps with developing characters so they don’t all sound like me, not to mention the utility in ghost-writing.

• As a negative, I’m not comfortable with taking mad leaps in writing. I’m never going to be able to write something like “the blue-green leaves of the live oaks made a brushing sound on the tin roof that sounded like soft crying.” My writing and descriptions are spare and I’m not sure I can do much about it.

• The positive side of that is that it’s almost impossible for me to write without having a complete picture of the characters, the setting, the time of day, who is standing to the left, who is holding the gun, etc. It’s the effect of years of writing to pictures and I’d hope it would make my books perfect for a great movie (Anyone listening in Hollywood?)

• Finally, I know that when I sit down, put on headphones with boring music, and put my fingers on the keys. I WILL write something. I’ve sat and crafted 70 minutes of stand-up comedy without ever having written a single joke before, I’ve written moving obituaries about people I’ve never met, I’ve written entire 60-minute documentaries in less than a day. I’ve dictated material off the top of my head that went on the air seconds later. Writer’s block simply isn’t allowed in a newsroom.

Graham Greene famously wrote, ‘There is a splinter of ice in the heart of a writer.’ What do you make of his observation?

Marshall Frady, who was a real journalist for many years before he came to television, told a story about himself. He was assigned to write a long magazine piece about some Senator or another so he went and met the man, they ate dinner, they smoked cigars, they got rip-roaring drunk, and stayed up all night telling stories. A day or so later, when he handed in his copy, the editor looked up from reading and said, “Wow, this is tough. I thought you liked the guy.”

Marshall said, “I like all of them before I sit down at the keyboard.”

Greene was talking about the writer’s instinctive desire to observe the emotions of those around him or her, rather than to share those emotions. Journalism and creative writing have a lot in common in this. A journalist has to be able to get close enough to his subjects to truly understand them and yet step back and write–not from the subject’s point of view–but from the journalist’s. One of the toughest assignments is to ’embed’ with a group of the military in the past two wars. Not only is the journalist living with these people 24 hours a day, sometimes for weeks, but they are depending on them for their very survival. I would say that the vast majority of journalists embedded came to unconsciously reflect a distorted vision of the facts–distorted in favor of the troops.

(One of the few contrary examples was Kevin Sites who was a single cameraman/reporter embedded with Marines in Fallujah and who showed pictures of prisoners being shot while they lay wounded on the ground. His book, The Things They Cannot Say, details this story and the agonies of PTSD it engendered in both journalist and marines. An excellent read for anyone interested in the reality of war. The marines understood the rules of engagement to be “No Prisoners” and were probably correct in their understanding of what the commanders on the ground wanted.)

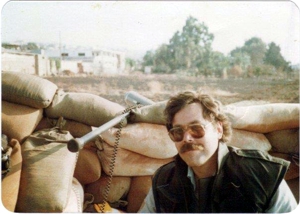

I was never a war correspondent. When the Marines left Beirut in 1983, one of them said, “So what are you going to do now that we’re gone?” I responded, “I’m going back to my hotel. You guys out at the airport didn’t have much to do with protecting me.” Lebanon was a strange situation, the US kept attempting to turn it into a simplistic “us vs. them” battle when there were at least 3 opposing sides and betrayals usually happened twice a day. I left after three months with a complete awareness that I knew less about what was really happening than I did when I first arrived.

I was also never an investigative reporter. To do a good investigation, you have to destroy someone. The factory owner, the labor leader, the politician, whoever. You have to get close, find the facts, and then reveal all their weaknesses and crimes, and keep driving in the nails until they’re left bleeding on the floor. I simply never had that sort of blood lust. I generally did stories that said, “This happened. This is what was behind it. This is what it could mean.”

I write fiction in much the same way. The villain in “Courier” is human. He is loved. An event that happened long ago in Korea was responsible for ‘freezing’ his soul. He does his work because if he didn’t, he couldn’t live with himself. He has to believe that what he’s doing is for the Good of the Nation. In that, he’s like any other soldier and especially like Rick Putnam, the protagonist. Rick is struggling to live with his actions in the Vietnam conflict and primarily, trying to live with his killing of another human being. I had a brief argument with my editor who wondered why Rick wasn’t tougher, why didn’t he fire back? Well, Rick’s entire problem stems from having killed–he’s extremely unwilling to kill again.

So, the ice in the soul. I think most, if not all, good writers (and, no, I’m not putting myself in that group) have to be more inclined to watch people cry than hug them, more apt to take a picture of human misery than to do what little one person can do to alleviate it. Otherwise, I don’t think you can see beyond yourself, you can’t understand and describe how others react in a crisis.

I’m reminded of Robert Capa’s famous picture of a Spanish Republican soldier taken in the instant that a bullet entered his brain. Capa believed in Spanish democracy but if he hadn’t stood back and observed, we’d never have had that evocative image of war–or the pictures he took of the D-Day landings that showed the insane bravery of American troops advancing and dying in a storm of bullets.

(Now here’s a tragedy for you. Capa sent back roll after roll of film from Normandy but the lab assistant was so excited and nervous about the first pictures off the beach that he overheated the negatives and the vast majority were destroyed.)

How do you view Michael Herr’s Dispatches, as a novel or a work of journalism, and what is its place in Capote’s legacy?

Dispatches had a tremendous impact on my view of both the Vietnam War and journalism. When most of the journalists–although not staying in Saigon and drinking at the Caravelle–were going out with the troops and dutifully reporting what the military PAOs were telling them, Herr gave a complete picture of the war from the ground level. His honest and clear objectivity (in that he was pre-disposed towards facts and had a problem with both American lies and Communist ones) gave a reality to the reporting that provided far more information than the official, and usually incorrect, mainstream reports. In addition, the sheer joy he exhibited in the process of catching a ride on a chopper and going somewhere, anywhere, and covering what was there to be see, gave me a picture of journalism that I’ve never been able to lose.

(I saw something like that in Beirut when the Battle of the Camps was going on 100 miles north in Tripoli. A young man, couldn’t have been 22, was standing outside the Commodore clutching a single Pentax and asking car after car if they had room for another rider. No accreditation, no company behind him, no guaranteed sales. A lot more gutsy than I am. As was Marshal Frady. He walked into Havana at 20 and demanded to know where he could find Castro up in the mountains. THOSE guys are both journalists and genuinely insane people.)

Truman Capote, or as we call him “Dill,” went as far as possible in the other direction in “In Cold Blood.” As opposed to the personal and internal thoughts and feelings that Herr surrounded facts in Dispatches, he attempted to present the facts of the murders in a monotone, “just the facts, ma’am” manner and eliminated the slightest aspect of the personal. Yes, when you read it, you feel as if you are getting the pure truth, the whole story without any error or prejudice, but you could also write a book of lies in the same manner and give readers the same impression.

I guess you could pose them as opposing poles of 1970’s journalism but I would prefer to see them as simply two of a thousand ways to write and ways to understand an event. One is no more intrinsically true than the other. I’ve held for decades that the only way for a reader to even approach an accurate picture of an event, a cause, or a person is to read as many different authors on the subject as possible, read everything from the wire stories to the historical retrospectives, and all the magazines, satires, and puffery in between.

And then admit that you have still not achieved Truth.

Hell, I don’t know the truth about myself on most days. Despite the fact that I interviewed a number of those directly involved in the 1946 Event at Roswell long before they became media darlings, I don’t know the Truth of what happened. Despite the fact that three closely-spaced US military slugs in the forehead killed former NFL player Pat Tillman, I don’t know for a Fact that he was deliberately and not accidentally killed by one of his own troops.

Do you think the real is harder to define and portray in today’s society given our immersion in the internet and an envelope of propaganda?

Richard, that really is an excellent question and it reminds me of a book. It’s called “Courier” and is available on Amazon and all the other electronic outlets and at most Barnes & Noble stores. If your readers cannot find “Courier” at their local bookshoppe, I’d appreciate it if they pounded their tiny fists on the counter and demanded that the proprietor lay in a dozen copies at once. It has a solid 5-star reviews featuring such comments as:

• “Courier is Terry Irving’s debut novel and it is fantastic.”,

• “a ‘hold on to your hat’ fast paced thriller from start to finish”,

• “this book is entirely believable, scary, and thrilling. Irving is in the top tier of political-mystery writers.”, and

• “Oh, Terry, what a devil you are. All those years in the news biz and here you had a page-turner in your brain, just waiting to be written. Count me among the fans.”

Trust me, folks, it’s a fun read and written specifically to keep you amused during a long flight–as a matter of fact, anyone who sends me a pic of them reading Courier on an airplane will receive a unique and a collectible key chain which will undoubtedly become extremely valuable in the future.

Now, what were you rattling on about, Richard?

Oh yes, the pernicious Internet and the all-pervasive propaganda that crushes the individual in modern society. I’d have to say that this is a fairly widespread example of what I call the “Golden Dawn” fallacy. This is where every generation believes that their life is terrible and things like youth crime, lewd clothes on young girls, and all-pervasive propaganda were simply unknown only 20 or 30 years ago.

Odd that “20 or 30 years ago” would be the childhood of the doomsayers who make these statements, isn’t it? Yes, folks, youth crime is down, drunk driving is down, girl’s clothes may be lewd but they aren’t soliciting for sex on the streets below the age of consent as much, and propaganda is nowhere near as effective or pervasive as in earlier periods. The immediate past always seems better because it was a time when your parents dealt with all the world’s problems and didn’t discuss them with the kids. This creates a wonderful, “Wizard of Oz” view of the past that is only smeared with grime if you live long enough to get around to reading your parent’s letters and perhaps a history or two and realize what real conditions were “in the good old days.”

Sadly, I’m old enough to have done all that. Let’s begin with the internet and propaganda because the meaning of reality could take a bit to get through. During World War 2, American propaganda was the best in the world, created and produced by Hollywood’s best and incredibly effective. Once war with Germany and Japan was declared, the nation–which had been widely divided about entering the war and where the German Bund held massive rallies in support of Hitler–was quickly and completely turned into an efficient machine for producing goods and soldiers in an effort so massive that it was only surpassed by the Soviet Union (and the Americans didn’t have to shoot nearly as many people to get it done.) From Donald Duck to Bugs Bunny, geniuses like Dr. Seuss produced film after film, book after book, and article after article on the rectitude of our cause and the need for public sacrifice to achieve a better world. News was barely censored because the journalists–patriots all–did it all themselves, only giving the folks at home good news and heroic stories. It took the massive disaster of the botched beach assault on Tarawa where Marines walked over hundreds of yards of coral in the face of withering machine gun fire to produce the first pictures of dead soldiers (delicately covered by a veil of sand.)

Britain was no slouch at propaganda either. In fact, a great deal of Hitler’s Mein Kampf was devoted to the failure of German leaders to match the onslaught of posters showing German barbarians slaughtering Belgian nuns and his determination to match the enemy lie for lie in the next war.

In fact, American propaganda was so massively successful that many of the very men who produced it who were pivotal in the banning of propaganda aimed at our own population in the post-war years. (Interesting side note: When the sainted Edward R. Murrow took over the Voice of America, he said very clearly what he was creating. It was only when they created the Edward R. Murrow Center for Public Diplomacy that a new term was coined for what Ed simply called “propaganda.”) Now, despite constant efforts from people like the odious Dorrance Smith (the executive in charge of American Information in Iraq who called “traitors” any reporters who were less than enthusiastic about the glorious victories in the Second Gulf War) there is very little direct, paid propaganda sent to American homes. The news media does provide a fairly open loudspeaker for the administration’s position but there is at least a bit of dissent allowed for flavor and spice.

In fact, Americans have had a clearer picture of Iraq and Afghanistan than of any other conflict in American history. This is due to the military’s decision to “embed” reporters with troops and an extremely open attitude by American troops to call a spade a spade and a snafu a “situation normal, all fucked up.” An example would be the soldier who stood up and berated Don Rumsfeld over the inadequate armor on HUMVEEs being sent into active battle zones.

Which brings us (or at least me) to the question of reality. The internet has supplied the information consumer with more and more varied pictures of what’s really going on than at any other time in history. Compare our information age to a French peasant’s view of the cosmos under Louis the Sun King, or the average American under the biased newspapers of the Hearst and Pulitzer. You don’t have to read all the differing views of reality but it’s out there and more people read more than ever before. You even have war reporters who support themselves through online donations and report whatever they damn well please. (Michael Yon and Kevin Sites would be examples.) In the domestic world, you have independent groups and consortiums like the Center for Investigative Reporting (read Chuck Lewis’ recent book for a clear view on how much of a Potemkin news village network investigative units have always been.)

So, the internet is a relief valve for information. Wikileaks, Edward Snowden, and even the ubiquitous news bloggers provide– if not unbiased, at least varied–view of reality. The fact is that there has never been a period in history when so many knew so much about ‘Wha’s Happenin.’ Now, the fact that many of these same people complain mightily that some of that information doesn’t match their particular religious, political, or personal viewpoints is only proof of its potency.

I mean, 90% of American Catholics don’t agree with the Vatican on reproductive rights. In earlier times, disagreeing with the Vatican on much less substantive matters is what led to the Hundred-Year War and the mass migration of religious dissidents to America where they very wisely attempted to remove religion from the list of thought crimes for which they were allowed to burn each other.

If that’s not progress, what is?

What are your views on the NSA?

The NSA is a lot like the Atomic Bomb, once you have the technical ability to do something, you will eventually be forced to do it. You’re forced by either the threat of an opponent developing the same technology or by the fact that a bureaucrat who does something, even something stupid, about a problem is better off in the face of disaster than a bureaucrat who realized how stupid it would be and didn’t do it. I would also suggest that other nations, like Europe, not be too terribly smug about how the USA is the only unethical criminal in the intelligence field–if they aren’t running their own surveillance operations– it’s only because they are getting the information from the US and it’s cheaper that way.

I think the evidence is fairly clear that the intelligence community has lied, sincerely and convincingly, about everything always. When Secretary of State Henry Stimson declared that “gentlemen do not read each other’s mail,” and closed the Black Chamber (America’s World War One office of signals intelligence), it didn’t close. It simply moved over to the War Department’s Signal Corps and went on merrily decoding the diplomatic and military signals of both friends and enemies. According to Jim Bamford’s classic book, The Puzzle Palace, there were even more parallels to today’s situation. One of the original founders of the Black Chamber decided to publish a book containing all the Japanese diplomatic cables. It was tremendously popular with the public and the government moved heaven and earth to get it banned.

Sound familiar?

I used to work for a dot com that was ensconced in an office one floor above the labs where Booz, Allen, Hamilton contractors were building CARNIVORE, the first system the FBI developed to read your email. (Slash Dot, the hacker’s magazine, reported that CARNIVORE was installed in all major internet connect points on 9/12/2001, the day after the terrorist attacks on New York and Washington.) One day, the building management called a fire drill and, in an attempt to get engineers to leave the building for anything less than the sight of flames, provided an ice cream truck in the parking lot. One of the other employees of our streaming media start-up nudged me and asked, “Do you think our national email system is safe with all these guys out here eating ice cream?”

I guess what I’m getting at is that most people expect that the government is listening in, it makes them feel safe, and if–as in the case of 9/11–it turns out that the government hasn’t listened in enough, they complain vigorously. There is a good deal of hand-wringing going on right now but I doubt that any vaguely intelligent U.S. citizen is really surprised by the fact that the NSA’s PRISM computers out in Idaho are sweeping up every phone call, email, tweet, Instagram, and document it can find. I mean, what the hell did anyone think they were going to do with several petaFLOPs of computing power?

Play video games?

The hope is that, given enough intelligent protest, the people at the sharp end of the spear–analysts, supervisors, lawyers, etc.–will be forced to at least pretend that they didn’t hear you talking to your girlfriend when your wife wasn’t home. Ever since Windows 95, I’ve assumed that someone was perched in my computer and that feeling has only increased over the years. For decades, I’ve lived by the simple rule that you never put something in a computer that you don’t want to see on a future employer’s desk, as evidence in a trial, or sent anonymously to your significant other.

It’s not just computers. The first thing I thought of when I saw EZ-Pass electronic toll lanes pop up in New York was their use as a tool to establish where you were and when. Sure enough, they’ve been used in everything from divorce trials to insider trading prosecutions. So has the use of a cell phone which conveniently keeps track of where you are, who you talk to, and, probably, your heart rate and hormone secretions. That guy at the car rental counter knows where you drove, how long you were there and how fast you were going. Most cars now record the final seconds before an accident–try telling the officer that you were only going 35 miles per hour when your own car is shouting, “He’s such a liar!”

Like all whistleblowers, Assange and Snowden will be pursued and vilified as traitors and, equally, will be quietly thanked by the citizens who now know a bit more about the secrets and lies that government officials tell. In Courier, one of the things that’s in the subtext is the 1970’s change from the Praetorian viewpoint of “We know what to do and we’re going to do it no matter what some stupid law says” that was essential during World War 2 and had grown to be completely out of control in Nixon’s criminal administration. Watergate, like Wikileaks and the latest NSA revelations, created a widespread revulsion and, eventually, new and stronger laws. These new laws never actually stop government restriction of individual rights but they do back them off for a while.

Yeah, we live in a society where less and less is actually kept private.

Yes, it’s approaching Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon

Yes, the unofficial motto of the government is”If you’ve done nothing wrong, you have nothing to fear.”

What’s your point?

I used to believe that the parents of every child should provide them with a second birth certificate so that they have one chance to disappear and re-invent themselves if their world falls apart. Hell, that’s what drove the explorers and immigrants who built America not to mention those criminals who built Australia into a haven for beer and beach volleyball.

I can’t imagine that we will ever see a world with zero nuclear weapons. The technology exists and, unless the benefits are vastly outweighed by the costs–as in the cases of South Africa, Brazil, and Libya–any nation that can muster the resources will eventually have at least a bomb or two. On the other hand, we haven’t had the type of world war that used to decimate every preceding generation of young men. It will be the same with the ability of governments to listen in on its citizens–if they can do it, they will. You just have to work to ensure that the person listening is either ethical or sufficiently scared of going to jail that they will use the data properly.

My old boss, Ted Koppel, went to Romania after its unspellable dictator fell. The first day they were there, the manager of the hotel showed them the small room where the secret police used to sit and listen to microphones in every room and taps on every phone. Four days later, when Ted and Nightline were leaving, they went back to the small room. Guess what? The door was locked and, after some knocking, a uniformed policeman of the new regime came out and told them that they were not allowed in the room and nothing was going on in there anyway.

Do you think this is an age of voyeurism?

Are we more voyeuristic?

Probably but it’s a lot less fun. Think of the thrill of a peek at a Playboy in the drugstore, paying a quarter to see a cootchie cootchie dancer at the carney, or spotting when a girl on campus forgets to pull her shades down. Now compare that to the deluge of pornography that hits anyone over the 7 when they turn on a computer.

Sex with elephants? Right over here!

Sex with Grandma? Oh, that’s just down there.

It’s enough to turn one into a monk if your libido hasn’t already been damped out by your anti-depressants.

And then, there’s Woman’s Erotica! Now, instead of fantasizing about copping a feel of that virginal armful at the movies, you find out that all she really wants is to be whipped and if your equipment doesn’t measure 10 inches, you can just forget about playing the game at all. I used to think I understood women. Now I just accept them as another species–with equal rights of course–but about as understandable as ethereal entity from Alpha Centauri.

So, are we more voyeuristic? No. If anything we know far too little about our neighbors and far too much about people we don’t give a damn about. Computers have given us the ability to peek into anyone’s private world and, guess what we found? It’s just as boring as ours. I mean, do you really think that Chancellor Merkel had anything interesting to say in the phone calls that the US tapped? At least when you Brits were hacking the Royal’s cell phones, there was a frisson of illicit interest although you have managed to make them as “common” as any “commoner” in record time.

No, like cotton candy, illicit knowledge of the Other is only interesting in inverse proportion to the amount we get to know.

Poets would write odes to the ineffable and unknowable hearts of their pure and heavenly loves. Now they can just check her relationship status and see if she’s “unfriended” the other guy.

Going back to the previous question, as a special treat, I’m giving you a peek at my next book, a paranormal thriller where Magic strikes Washington–and the NSA at Fort Meade. (Barnaby is the first program ever run at Fort Meade, Steve is a journalist who has become America’s Last Wizard, and Ace is a woman who was a SEAL until her homemade spell slipped and they realized she wasn’t a man.)

Going back to the previous question, as a special treat, I’m giving you a peek at my next book, a paranormal thriller where Magic strikes Washington–and the NSA at Fort Meade. (Barnaby is the first program ever run at Fort Meade, Steve is a journalist who has become America’s Last Wizard, and Ace is a woman who was a SEAL until her homemade spell slipped and they realized she wasn’t a man.)

“If I could interrupt?” Barnaby said from the speakerphone. “I think we should all remember that 481 passengers and 12 crewmembers on American International’s Flight 1181 were either killed by the Illuminati or by people they’re working with and we don’t know what they have planned next. Perhaps I’ve been affected by the general attitude around Fort Meade since 9/11 but I can’t see these people as anything other than dangerous terrorists. I’m not saying that summary execution is in order but arrest and a fair trial, followed by a sentence of life without parole in the Florence, Colorado SuperMax wouldn’t be a bad idea.”

“Haven’t you been able to listen in on them or read their email with all those supercomputers of yours?” Steve asked. “If you don’t know what they’re doing, what has been the point of this Bentham’s Panopticon society you’ve been creating?”

“As we say, ‘if you have nothing to hide, you have nothing to fear.'” Barnaby said. “However sadly, we can’t pick up their communications. They aren’t sending emails or using cellphones and, as far as we can tell, they never have. Now that doesn’t mean that some of my brighter colleagues haven’t been trying to crack their communications with all the new mystic methodologies. It’s been a completely new project and several of the servers have blown and one or two can’t really be described as ‘computers’ anymore—as a matter of fact, I’m fairly sure that they’ve completely discarded their physical forms and just come back every once in a while to chat. Apparently, the plane of pure consciousness is a pretty boring place.”

“Off topic.” Ace said abruptly.

“Yes. Yes. I am.” The computer admitted. “The point is that the STORMBREW system out in Utah is reporting that they’re having success with what can only be described as ‘séances’.”

“You’re kidding.” Steve said.

“No, I’m afraid I’m not and if you’ve never spoken to an opportunistic distributed system made up of Cray Titans, IBM Sequoias, and Chinese Skyriver 2’s as it’s trying to climb down from the yottaFLOP range, you have no idea what ‘spooky’ means. STORMBREW managed to speak to Harry Houdini a couple of hours ago and is now sifting through approximately 5,000 spirit guides a second. STORMBREW turns out to be an amazingly apt codename. I mean, there are data halls where the danger from floating tables alone—”

“Off topic.” Ace repeated.

“Yes. Well. The point is that there is some success in breaching the communications of… Well, Stormy, that’s the nickname it chose, is fairly sure that 1) it’s communications, 2) it’s coming from here on Earth, and 3) it ‘feels’ like the Illuminati but beyond that it’s not really very clear.”

“I’ll say.” Steve said dryly.

“This should be easier to understand.” The computer continued. “Two of the more energetic sub-clusters—BLARNEY and OAKSTAR—report hearing chatter indicating another event being planned that is similar to the American International crash but far more powerful.”

“How much more powerful?” Steve asked.

“In the kilo-logos range.”

“‘Kilo-logos’?” Steve said slowly.

“Yes. From the Greek word for ‘soul’.”

“I hate to ask, but what was the American International event on this ‘kilo-logos’ scale?”

“Tragic as it was, it only measured .043.”

“So we’re talking about a hundred thousand lives?”

“One hundred thousand souls, to be precise. However, discounting the odd person who is currently possessed by a demon or collateral damage among household pets, yes, a hundred thousand people will die.”

Ace went back to her gear and began to replace various rounded, flattened, or rubberized items with those with sharper blades and barbed razor-points.

What are you working on right now?

If I intend, as I do, to make a living off of my writing, my working assumption is that I’ll need to create 4 to 5 series and publish 3 or 4 books a year. In a few years, I’ll have a relatively stable income due to the “long tail” effect of online sales and print-on-demand. When I was told that the sequel to Courier wouldn’t come out until February of 2015, I immediately began working on other projects rather than complete the third book in the series.

So, at the moment, I’m working on:

1) The Third Freelancer book. This is as yet unnamed because after Courier and Warrior, I’ve only thought of Janitor and I don’t think that will work. I do know that the book will take place in New York City circa 1974 when Manhattan was dirty, crime-ridden, and a lot more fun. There was no Disneyfication of Times Square and you took your life in your hands every time you went down there to slake your evil desires (in my case, by playing pinball.) I can still remember going down to a New Year’s Eve ball drop and hearing the smashing of glass bottles as a continuous noise, like surf hitting the shore. There were cops in orange wool hats in the crowd and occasionally they would toss some malefactor over the barriers into the cleared center aisle where the police on horses and motorcycles would hustle them off to captivity. I’m doing a slow research process on this because of the far-off publication date but I think the plot will center on a murder of a B-level celebrity and a sequence of events that will lead to the CIA’s movement of their drug business from SE Asia after the Fall of Saigon.

2) “The Day of the Dragonking: Book One of the Last American Wizard” This is a paranormal thriller in a light vein. A 9/11 style attack is made on Washington but it’s a mystical attack–actually a sacrifice to the Worm Ouroborus–and it unleashes Magic into the political equation. This one is actually near the end of the second draft so it’s fairly complete. The concept is that anyone (except the Bad Guys) who had a bit of magic before has lost it and only one man–a bored and cynical journalist–is now a full Wizard. In this world, whatever power you held before (financial, political, computing) has become Magical Power. So a powerful computer is now a sentient computer, a powerful Republican Congressman is now a Dwarven King, the Democratic President is an Elf Queen. In addition, it’s a Aristotelian world with Air, Water, Earth, and Fire as the central structure and various editions of the Tarot as the guides.

Once you scratch the surface of American history, Freemasons and other occult and spiritualist groups just come flying out by the dozens, so they end up playing a large role as well. (Here’s a question: secret societies were an enormous force in American Society right up until World War 2 with hundreds of thousands of members. Why have they now been relegated to funny men in tiny cars who drive in parades?)

In any case, our intrepid journalist, Steven Rowan, has unwillingly taken on the role of The Fool from the Tarot and is tracking down the miscreants with the aid of Ace Morningstar, a beautiful blonde woman who, up until the Change, was a tough and resourceful Navy SEAL with just enough magic to disguise her femininity, Barnaby, who has taken a leadership role among the squabbling computer minds of the NSA, Send Money, a cell phone haunted by the ghost of a young Chinese factory worker who committed suicide just as that particular phone was completed, and Hans, a BMW 5-series with a rather touchy and demanding Germanic personality.

3) Pearl of the Orient: I’m planning and researching a private eye series based on the research I did a couple of years ago for a documentary (Rescue in the Philippines: Refuge from the Holocaust.) We interviewed the daughter of a Greek-American private eye for that film and she gave me permission to use her father as a prototype for the role.

Manila in the 1920s and 1930s was a fascinating place: the Americans were pulling out as fast as they could and building up Philippine institutions to replace them, the Filipinos by and large were very pro-American (“After 400 years of the Spaniards, the Americans were nothing.”) so there is a hybrid society of zoot suits, nightclubs, and beautiful women, a president who was also the nation’s best tango dancer, and unenforced immigration laws that resulted in the entrance of Chinese tongs, Japanese spies, Jewish refugees, White Russians, Javanese, Germans, and a lot of Americans just out to make a fortune in a faraway land. The cool thing is that everyone is thousands of miles away from their bosses so that the American High Commissioner is refusing direct orders from the State Department, the German Consul is treating Jews reasonably against the order of the Nazis in Berlin, and the Filipinos are living in a delightful stew of indigenous and adopted cultures.

4) YA Dystopia: All I know is this category is selling like mad so I’m laying down the most basic foundations for a series. It depends on the 1% of the 1% continuing with the concentration of wealth, reducing even middle-class Americans to dirt-floor and subsidence farming levels of poverty not seen since the Great Depression. A brother and a sister are orphaned when their parents – dismissed from their jobs – commit suicide. Along with a small group of friends and other malcontents, they decide to seek revenge and reparations. If nothing else, it should have nice locations to research (Hamptons, West Palm, etc)

What advice would you give to yourself as a young man?

“Suck it up and go to Law School.”

I’m completely serious. I don’t go to my college reunions anymore because half the class went on to four more years of (fairly easy) training in law or business and now they are absolutely rolling in money. I went off and did exactly what I pleased for 40 years, travelled a good deal of the world, raised children, wrote things I never thought I could write and accomplished things I never dreamed of accomplishing. In the end, however, I have about $100,000 in the bank, two kids who still need financial support, a small-ish house, a small-ish car, and a lovely wife. It’s a good life, but I would really like to take a vacation or even a weekend at the beach without having to consider the cost.

There was a point when I was running around with scripts and coffee as a Desk Assistant that this thought occurred to me. Suddenly I felt that I should stop fooling around with this childish stuff and go to Law School. Unfortunately, I had been one of the first paralegals anywhere and I really hated it. I worked in an enormous firm (for the times) and hundreds of idiot lawyers were swotting away around me trying to make the world safe for tobacco, coal, and international conglomerates. (One or two of them did have wilder dreams–one actually became the attorney for the natives of the Natives of Bikini Atoll and successfully sued the US government for leaving the place a deadly, glowing nightmare. Quite forgot their promise to return the atoll in the same condition they obtained it after a couple of hydrogen bombs were gently deposited in the lagoon

While I was a paralegal, my (then) girlfriend and I were assigned to four months of reading letters of complaint to the Federal Trade Commission about mail order frauds. As I remember, she broke down in tears a couple of times and, since this was in the days of Jimmy Carter and energy conservation, I had terrible headaches because they had removed every third fluorescent bulb. I would stand outside smoking a cigarette and watch the couriers speed past. They were free, in the sun and air, and headed to earth-shattering events of some sort or another. (As it turned out, the overwhelming complaint was about a scam where an ad would appear in the newspaper saying, “Want to Make Money from Home? Send $1.00 to the following address.” If they bothered to reply at all, the hucksters simply sent back a note that started, “First, place an ad in the newspaper that says ‘Want to Make Money from Home.”)

Of course I grabbed at a job when they offered it to me. Who wouldn’t trade the stuffy life of an attorney for the freedom and general wonderfulness of being a journalist?

Then I spent the next 8 years in dark rooms, generally between the hours of 2AM and noon, working with grumpy men with the underlying personality of aging wolves. They were engineers and had already been placed on the worst possible shift and were basically unpunishable. At 8am every morning, when the morning news reached its shrieking crescendo, they would begin to turn up the volume on their playbacks, bang the loose steel doors of their edit machines, and place random phone calls to my phone–hoping to see me shatter into a sobbing, broken lump of flesh in a ratty necktie.

I do mean EVERY morning.

After that, it was a lark to volunteer for the presidential campaigns. The 1980 Campaign was like no other before or since. Ted Kennedy was running (finally) and every news director was sure someone would shoot him just like his brothers. (I personally think that the criminal/terrorist community realized faster than we did in the press what a worthless fool Ted Kennedy was and decided to leave him alive to wreak havoc on his own party.)

On a good day, two of us field producers would have under out titular control two correspondents, two cameramen (who, because of union rules, were making twice my salary), a radio correspondent, two soundmen, and a lighting technician. I used to carry around a couple of thousand dollars in cash because the Kennedy campaign (which never had a ghost’s chance of winning) would periodically run out of money and demand that the press pay upfront for the next bus or airplane or whatever. We never flew the same airline twice in a row because of unpaid bills and once we were booked on the old Evergreen Air–the boys who used to fly the CIA around Southeast Asia. Another time, we were about to take off and I noticed all our camera gear left on the tarmac. I had to jump off the plane and shepherd the 26 cases up to the next stop without actually touching any–that would have been a union violation.

The end result of all this was a complete case of twitching neurosis. I had lost the habit of eating breakfast or lunch, I smoked six or seven packs of cigarettes a day, I didn’t have any friends except for my girlfriend, and I would wake in the middle of the night standing in the middle of my bedroom making little mewling noises and trying to work out what city I was in. This, of course, made me a perfect candidate for Nightline where the hours were much longer (although still at night, you’ll notice) the expectations were far higher, and the competition more intense. I mean, it was fun and all and I did win a bunch of awards but there was a bit of blood left on each one.

Enough whingeing.

I got to see the Berlin Wall go down from the East Berlin side,

I was in South Africa during the worst of apartheid and on the day Nelson Mandela was released,

I sat in Hong Kong and mapped every minute of the action in Tiananmen Square (including the oft-missed final exit of all the students at around 5am which was only shot by a single Spanish film crew).

I got to spend a day in the Shuttle simulator before the first launch (what a laughable antique that would be now) and years later heard “the tearing of God’s own Velcro” when the first Space Shuttle after the Challenger disaster leapt into orbit.

I learned to start a day standing by myself in some rainy town and finish with an entire caravan of television equipment and technicians as we covered a prison break.

I’ve flown in most types of small aircraft–including a couple of Learjets (cramped) and watched RPGs spin in random spirals as they went over my head in Beirut.

I was either present or in a control room for most of the major events of my time and put together some stories that were both intelligent and, frankly, impossible in the time allowed.

And, I have to admit, most of the time, I wouldn’t have traded it for the world.

It’s only now, when I get to add up the sums that I regret not going for the money when I had a chance. But it’s a passing thing and I get over it fairly quickly.

I didn’t think I could write a book, either. In fact, most of my life has been spent proving to myself that I could do something that I didn’t actually believe I could do: write a book, write a good show about war every week for six months, run a TV show by the time I was 30, pull together a 7 camera remote out of London without a satellite path over the Atlantic, get picked up by South African secret police, get threatened with death by South African students and be rescued by someone who I took the time to have dinner with, get up every damn morning with crushing depression and still make it to the end of the day.

Put two kids through college, took care of two wives (one at a time) and paid every bill (eventually), got fired by Fox and had a job with MSNBC two days later, stood on a road in New Jersey realizing that I was completely alone in a brand new job and end up with a crew of kids that I trained and was so effing proud of you really couldn’t believe.

So, I would have told my younger self to go to Law School. I’m not sure I would have told him to be a lawyer. Wanting to go to work every day has its advantages.

And, of course, I got to ride motorcycles. Lots of different motorcycles. I don’t know if I would have had a bike if I was a lawyer.

That would really have been a shame.

Terry thank you for an insightful and comprehensive interview.

Links:

6 Responses to Chin Wag At The Slaughterhouse: Interview With Terry Irving